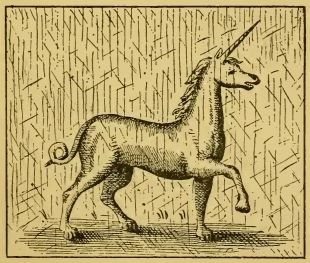

In the Classical world, the unicorn was not a mythical

beast because the ancients believed that they were real flesh and blood creatures. The first description of the

unicorn is in the writings of Ctesias, a Greek historian of the fifth century

BCE who is remembered largely for his unreliability. In his Indica, he

says that in India there are wild asses as large as horses that have a single

horn in their foreheads about a cubit in length, this horn is proof against

poison and is made into cups, the unicorns are very wild, are impossible to

take alive and that their flesh is inedible.

All the usual Classical suspects –

Herodotus, Aristotle, Aelian, Pliny the Elder and their ilk – take his word for it

and included descriptions of the unicorn in their works that can be traced back

to Ctesias’ original, although there are some embellishments and elaborations

of their own added. Julius Caesar, in Book IV of the Gallic Wars,

describes an animal that can be found the Hercynian forest of Germany,

“…an ox shaped like a stag, from the middle of whose forehead between the ears stands forth a single horn, taller and straighter than the horns we know.”

Conveniently, the inability to take a unicorn alive is emphasised, which

accounts for the lack of live specimens being exhibited in, say, the Roman

arena. There is a creature mentioned in the Bible – the Re’em – a name that is

sometimes translated as the unicorn, but the term is misapplied and refers

perhaps to some species of wild ox, the oryx or maybe even the rhinoceros

instead.

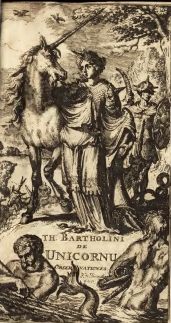

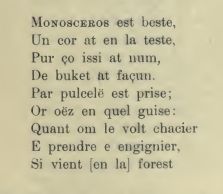

The unicorn moves into the world of myth and fable in the Physiologus,

an early (c. 2nd century CE) precursor of the mediaeval bestiaries,

in which a series of allegorical stories are related to Christianity, with

animals real and imaginary used as metaphors for Christian virtues and

attributes. The unicorn was introduced as a symbol of the Incarnation, a wild

beast that would only permit itself to be tamed by a pure virgin maiden,

reflecting how Christ allowed himself to be made flesh through his mother, the Virgin

Mary.

Stories like this were included in the later bestiaries, descriptions of

strange birds and beasts, which also included the myths surrounding their

subjects and which came to be regarded as fact. So, for example, the pelican

was believed to feed its young on its own blood, delivered through pecks it

made to its breast, something taken as fact long after mediaeval times.

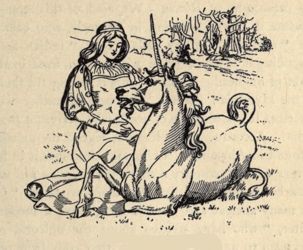

The

legend grew that the only way in which a unicorn could be caught was for a

virgin maiden to sit in the forest and the animal would approach her, place its

head on her lap and allow her to place a silver chain about its neck.

There are

a number of animals that could have been the ‘real’ unicorn, which were

probably seen by early travellers and their descriptions conflated with local

tales from natives to arrive at single horned creature.

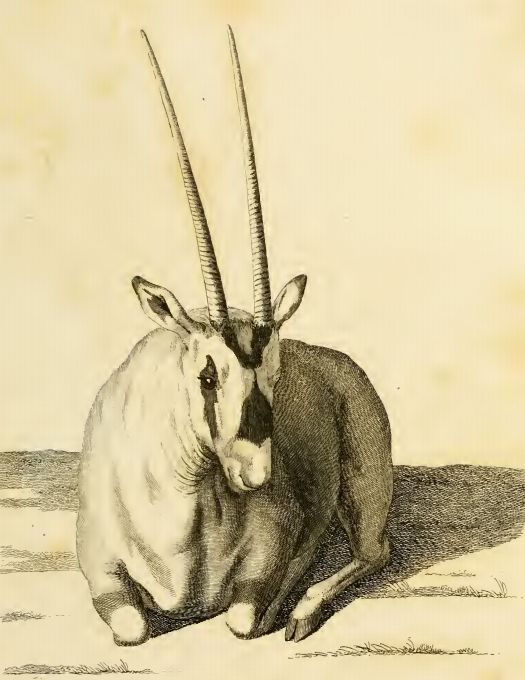

One such is the oryx, a

type of desert antelope that, seen from the side and at a distance, could be

mistaken for a monocerous beast, although its horns point backwards rather than

forward as in the traditional view of the unicorn. We can see from relief

carvings and paintings in ancient Egyptian tombs and temples that it could be

easy to mistake the double horns of the oryx for a single-horned unicorn.

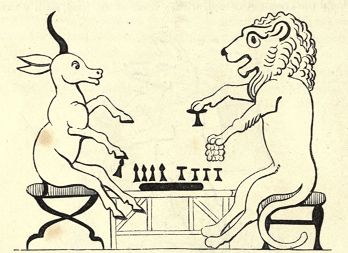

An

amusing depiction of a unicorn also comes from an Egyptian papyrus (in the

British Museum), where one can be seen playing a board game against a

(victorius) lion.

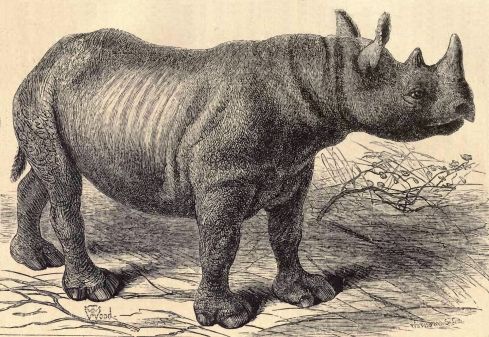

Another candidate is the rhinocerous itself, either single or

twin horned, that is, in spite of its bulk, a remarkably speedy creature in a

charge and again, seen at distance, could conceivably misconstrued as a heavy

horse-like beast. Other possibilities are a variety of horned cattle, goats or

deer, which could all be thrown into the mix and a zoological game of Chinese

whispers did the rest.

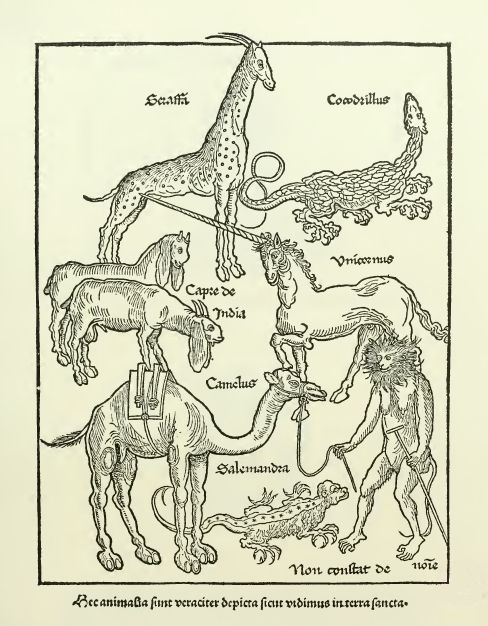

In one of the earliest travel books ever published,

Bernhard von Breydenbach’s Pilgrimage to the Holy Land (1486), there is

a woodcut by Erhard Reuwich that shows some of the animals seen on the journey

and in addition to a giraffe, some goats, a camel and a very strange crocodile,

there is a beautiful unicorn.

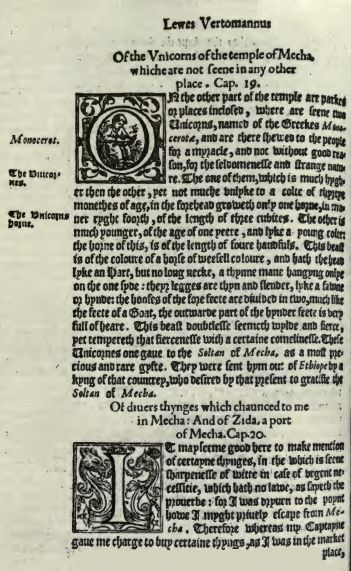

A slightly later traveller, Lewes Vertomannus,

wrote about a pair of unicorns he saw in a temple at Mecca, included in his

description of his voyages made in 1503. He says,

“This beast is of the colour of a horse of weesell colour, and hath the head like a hart, but no long neck, a thynne mane hanging only on the one side. Their leggs are thin and slender like a fawn or hind. The hoofs of the fore-feet are divided in two, much like the feet of a goat. The outer part of the hinder feet is very full of hair.”

Vertomannus says that these unicorns were presented to the Sultan of

Mecca by the King of Ethiopia, and later, after being driven by an ill wind to

Zeila, Africa, he writes about a market there, were he saw,

“…certain kyne [cattle], having only one horn in the middle of the forehead, as hath the unicorn, and about a span in length, but the horn bendeth backwards. They are of bright shining red colour.”

In 1622, a Portuguese Jesuit, Father Jerome Lobo, also

reports in his Voyage seeing unicorns in Abyssinia,

“In the province of Agaus has been seen the unicorn; that beast so much talked of and so little known … The shape is the same with that of a beautiful horse, exact and nicely proportioned, of a bay colour, with a black tail … They are so timorous that they never feed but surrounded with other beasts that defend them.”

Tomorrow - More Unicorns

No comments:

Post a Comment