Hardly had the Havells begun work on Audubon’s Birds

of America, than it dawned on the author that, of course, the Havells would

need to be paid. Audubon fell back on what he always did in such circumstances

– he improvised.

|

| J J Audubon - The Entrapped Otter |

The plan was to paint copies of his popular picture, The

Entrapped Otter, and hawk them around the various galleries and shops of

London’s East End, and he sold seven copies of the subject, together with

copies of other works. Then, Dame Fortune smiled upon him, when Sir Thomas

Lawrence, the renowned and celebrated society portraitist, called on him at his

studio and inquired about the price of the works he saw there.

|

| J J Audubon - English Pheasants Surprised by a Spanish Dog |

He departed and

returned later with two friends, who both bought paintings for twenty and

fifteen pounds respectively. Lawrence was back later with more friends, and

more paintings were bought for seven, ten and thirty-five pounds, leaving

Audubon with more than enough to cover the five pounds he had borrowed for

painting materials and to pay the Havells the sixty pounds they billed Audubon

two days later. It was a close escape, but the great work continued.

|

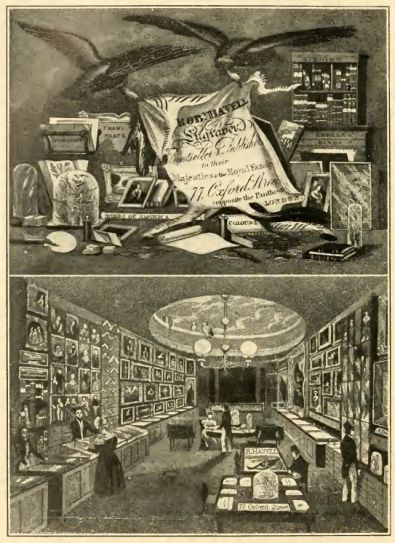

| Advertisement for Havell and Son |

He was not

out of the woods however. Subscribers cancelled their subscriptions, others

complained that all the birds looked alike and that the work was an out and out

swindle, agents appointed to collect the subscription money forgot to do so,

other forgot to deliver the prints, some of the prints from Lizars brought

complaints of poor quality and had to be replaced. Audubon took one of Havell’s

colourists to task about the quality of his work and told him to improve or

face dismissal, whereupon the rest of the colourists went out on strike in

support of their colleague, and it was several days before they could be

enticed back to work.

|

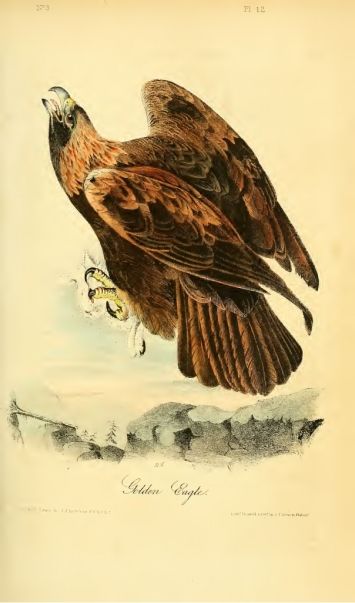

| J J Audubon - Golden Eagle |

In spite of all this, Audubon entered 1828 with his

finances in the black, confidence in his heart and hopes for the future in his

breast. He was still travelling incessantly, selling subscriptions and

paintings en route, and crossed the Channel, raising more subscriptions

and meeting the foremost French scientists and naturalists; the great Baron

Cuvier declared the work to be the

“…most magnificent monument which has yet been erected to ornithology.”

|

| Baron Cuvier |

Audubon secured subscriptions from King

Charles X, the Duke of Orleans, and swelled with pride when François Gerard,

the famous portraitist, seized his hand and cried,

“Mr. Audubon, you are the king of ornithological painters. We are all children in France and Europe. Who would have expected such things from the woods of America?”

The trip to

France cost him forty pounds and only raised thirteen subscriptions, but the

increase in prestige and reputation he felt had been well worth the investment.

He returned to London and left the publication to the Havells, in whom he had

now confidence, with Children as his English representative, and decided to

return to America.

|

| W H Holmes - Portrait of James Audubon |

On April 1st 1829, he boarded the packet-ship Columbia,

out of Portsmouth for New York, paying thirty pounds for his passage. On

arrival back in America, he paused to exhibit his paintings at the Lyceum of

Natural History, and settled for three weeks at Camden, New Jersey, where he

made some new paintings, before heading for Great Egg Harbour, and then to

Mauch Chunk, where he concentrated on smaller woodland warblers, finches and

flycatchers.

|

| J J Audubon - Common Buzzard |

In October, he turned south, pausing in Louisville to visit his

two sons before hastening to Louisiana, where he was reunited with Lucy. Before

long, he was on the road again, this time with his wife by his side, and in

April 1830 they boarded the Pacific in New York and embarked for London. After

a short stay, the pair left for Edinburgh, where Audubon began work on the text

for Birds of America, in what eventually became known as Ornithological

Biography (also called the Biography of Birds), a massive

five-volume effort amounting to over three thousand pages.

|

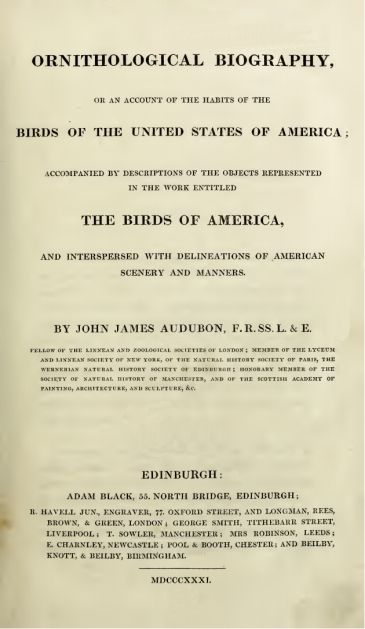

| J J Audubon - Ornithological Biography - 1831 |

In a brilliant piece

of recruitment, Audubon collaborated with a young Scots naturalist, James

MacGillivray, who was employed to revise and correct his text, at two guineas

per sixteen sheets. The two rose before dawn and worked late into the night,

writing the first volume in a mere three months, with Mrs Audubon copying the

text ready to be shipped to America, thereby securing the copyright. Unable to

find a publisher, Audubon paid for the publication out of his own pocket, the

first volume printed under the imprint of Adam Black, the subsequent four by

Adam and Charles Black.

|

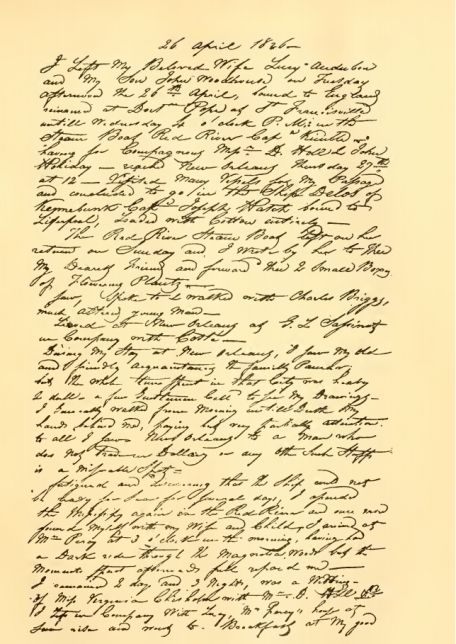

| Page from Audubon's Journal |

When the work was completed, the Audubons travelled

south, through Newcastle, York, Leeds, Manchester and Liverpool, and then to

London; Audubon relates in his Journal that they,

“… travelled on that extraordinary road, called the railway, at the rate of 24 miles an hour.”

After a brief visit

to Paris, they boarded a ship back to New York, and Mrs Audubon went on to

Louisville, to visit her sons, whist John began plans to go to Florida, to

paint the birds there.

|

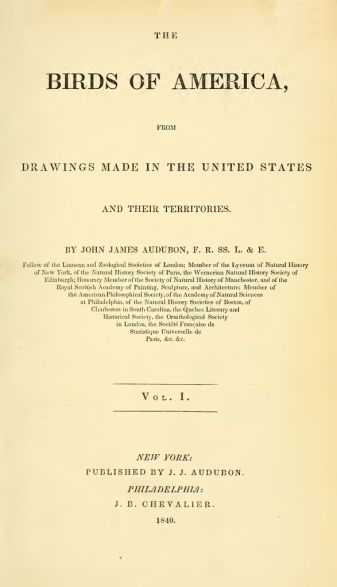

| J J Audubon - The Birds of America -Vol 1 |

On the same day they arrived in New York, the London

Literary Gazette published a notice of the death of the famous

ornithologist, Alexander Wilson. Immediately, letters were sent to the editor, pointing

out that Wilson the ornithologist had, in fact, been dead for eighteen years. A

red-faced editor printed an apology, of course he had not meant Wilson, he had

intended to write Audubon. More letters to the editor. What sort of a

newspaperman was he, to resurrect a man that had been dead for eighteen years,

only to kill him, and then kill another man who was, as all that knew him,

hale, hearty and just arrived back in America from England?

Tomorrow – Audubon alive after all.

No comments:

Post a Comment